How "Good Anxiety" Can Enhance Your Performance & Open The Door To Flow

You've probably heard that it takes about 10,000 hours of practice to become an expert in anything—a musical instrument, a sport, chess, cooking, or a foreign language. The research by K. Anders Ericsson on this topic has been written about many times, and it was made even more famous when Malcolm Gladwell described it in his bestselling book Outliers.

However, recently, a cohort of researchers reexamined the studies and research behind the 10K figure and said, quite dramatically, that the 10,000-hour rule was utter nonsense. Specifically, there is nothing particularly special about 10,000 hours, and while practice is clearly important to boost performance, other factors may play an even more important role.

What are those other factors that get us to expert levels of performance? Pure innate talent? Intelligence? Luck of the draw? Perseverance? Hard work? Yes, it's all of that...and more. Age, experience, and environment all play a role. In other words, there's no one certain factor that can predict or ensure mastery or optimal performance of anything.

The link between flow and performance anxiety.

The Hungarian-American psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi has led the charge in this area of affective neuroscience research—first with his studies of elite-level athletes but later applying how optimal performance can be seen in many areas, including science, art, and music. Flow is a spectrum. It's decidedly not an all-or-nothing experience. It's about the right blend of preparation, positive self-talk, and fluidity, and much of how it's activated relates to how we are learning how to unpack anxiety, its arousal, and its challenges. But this research is also relevant to anxiety; in particular, the elements or characteristics that enable flow align with how we can channel the arousal of anxiety. Being able to calm our bodies, nurture an activist mindset, and use our attention all come into play.

One new feature that flow calls upon is related to motivation. Flow requires that we become deeply engaged in and enjoy an activity, which is activated in part by the reward network of the brain. As we will see, anxiety can benefit this reward circuit or dampen it and therefore either enhance our performance or hinder it. Understanding the neuroscience of how anxiety (bad and good) interacts with the reward and motivation networks helps us to understand how we can use good anxiety to boost our performance and thereby have more chances to experience flow.

We can apply the neuroscience of optimal performance to anything we want to learn or relearn, any new skill or task we are curious about. The operative word here, however, is want. Using anxiety to optimize performance requires us to approach the task with enthusiasm and interest—not fear or reservations. In order to use our anxiety, we must befriend it. Let's look at how that can happen.

The neuroscience behind optimal performance (aka, flow, baby, flow).

I think everyone would agree that anxiety makes performance level go down the drain, so to speak. So regardless of your hours, months, or years of practicing a skill—whether it's public speaking, playing the piano, playing tennis or basketball—anxiety not only undermines your performance but absolutely eliminates any chance of reaching optimal performance or flow. But what I've come to realize from my deep dive into this research is that just as we can learn how to nurture an activist mindset, use mistakes or failures as feedback, and use the arousal of anxiety to up our attention, we can also learn how to improve our performance and perhaps edge a bit more toward a flow experience.

So what is flow?

Csikszentmihalyi and his colleagues, including Jeanne Nakamura, came to identify a state of heightened engagement or immersion in an activity that you are performing at a high level and called it "flow." Flow is defined as a deeply engaged state1 where high skill/performance accompanies a seemingly relaxed, almost effortless state of mind, one of intense enjoyment and immersion. They also note that states of flow don't happen every day. Instead, they are relatively rare occurrences that happen when the right combination of cognitive, physical, and emotional features almost magically align.

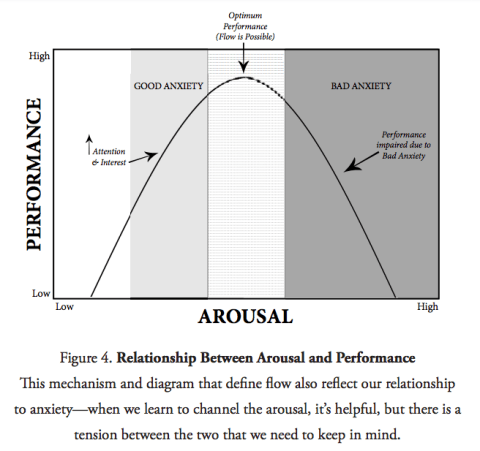

Studies focused on the relationship between arousal and performance have been going on for quite a while. Way back in 1908, something known as the Yerkes-Dodson Law was established by researchers at Harvard who were trying to understand what motivates goal-directed behavior such as studying in order to do well on a test. They wanted to understand whether or not stress played a positive role in motivation. What they learned is that there is an optimal level of arousal and its resulting anxiety that maximizes performance (high point on the curve of the graph below). But beyond a certain level of arousal, what we would call bad anxiety causes performance to plummet.

Let's spend some time looking at the left-hand side of this graph. The engagement piece implies enjoyment and pleasure. The arousal speaks to the need for some stress to provoke a state of alertness; this is the positive side of anxiety. Finally, it's the interplay of all these dimensions that prepares us or paves the way for that state of flow, where performance can be at its peak.

Note that good anxiety kicks in as the arousal level starts to increase, along with an increase in focus/attention. Arousal is measured in part by peripheral measures of autonomic activity such as heart rate and skin conduction. It's also measured by cortical activity that can be detected by an EEG. Alongside this recruitment of arousal (positive energy) and attention is our interest or degree of engagement. Together these factors help make the performance take a sharp upward trajectory. It's at the very top of the performance "mountain," so to speak, when performance is optimal, that you can experience flow. This graph illustrates very well why classic flow is not experienced very often. There are a lot of elements that need to come together in order to hit the pinnacle of true "Csikszentmihalyi flow."

Another element that can predict an experience of flow is improvement. Now, of course, "peak performance" is relative to any one person. My peak performance in playing the cello will always be wildly different from Yo-Yo Ma's, but the possibility of reaching my own state of flow regardless of my skill level adds to my motivation—I want to do better; I want to improve. This desire is what triggers the reward network. We remember the experience of pleasure because the brain releases dopamine, which in turn feels good. It's this good feeling that we remember and will want to repeat. The more skillful you are at something, the more efficiently your brain-body will perform. The more skillful you are, the more competent you feel. And the more competent you feel, the more relaxed you will be performing.

Looking again at the graph, it's important to note that we all walk a very fine line—you might call it walking on a razor's edge— between the point of optimal performance where flow is possible and succumbing to bad anxiety and the performance drop that comes with it.

Adapted from an excerpt from Good Anxiety: Harnessing the Power of the Most Misunderstood Emotion. Copyright © 2022 by Wendy Suzuki, Ph.D. Reprinted with permission from Simon & Schuster.

Dr. Wendy Suzuki is an award-winning Professor of Neural Science and Psychology in the Center for Neural Science at New York University and Seryl Kushner Dean of the College of Arts and Science. She is a celebrated international authority on neuroplasticity, was recently named one of the top ten women changing the way we see the world by Good Housekeeping and regularly serves as a sought-after expert for publications including The Wall Street Journal, Shape, and Health. Her TED talk has more than 55 million views. She is the author of Good Anxiety and Healthy Brain, Happy Life.